VPN services typically promote themselves for online security and anonymity, and access to geo-blocked content. And they typically brag about not keeping logs, high download speed, and diversity of server locations. Location diversity isn’t just a bragging point. That is, to maximize speed, one picks the nearest server that isn’t geo-blocked. So with lots of locations, there’s a better chance that some random user will find a nearby fast server.

Sometimes, though, the nearest server that isn’t geo-blocked is still on another continent. With that in mind, to provide better performance, some VPN services also offer virtual locations. That is, servers that aren’t located where they seem (more about that below). For example, a server may have a US IP address, and so provide access to US-only content. But it’s actually located near the user, or in some intermediate location, with good connectivity to both user and content server.

There are other reasons to care about where VPN servers are located. For example, some don’t want to use servers that are located in dangerous countries, fearing that they might be compromised. And so they would prefer virtual locations, that provide desired IP addresses without physical exposure. Also, with virtual locations, physical server locations are somewhat obscured.

However, different users have different ideas of which countries are dangerous. Some users consider the US and its close allies to be dangerous (see Five Eyes), having seen NSA stuff that Snowden released. But others prefer US servers, because there’s no legal requirement to retain logs.

Another obvious issue is money. For serving a given user base, it arguably costs less overall to run high-capacity servers in a few locations instead of low-capacity servers (or even VPS) in many locations. Although high-capacity servers do cost more than low-capacity servers, capacity vs price doesn’t scale linearly. One issue is fixed OS overhead. Another is fixed hosting overhead, which affects pricing.

There’s also the fact that using virtual locations allows VPN services to appear larger and more popular than they actually are. Even leasing the lowest-capacity servers that data centers offer, it’s unlikely that small VPN services could afford hundreds of them. But by using virtual locations, they can fake it. And that works both for new VPN services that are growing, and for established ones that are contracting.

Bottom line, there are pros and cons to virtual locations. For both VPN services and users. But the key point is that users deserve to know where VPN servers are located. And if there are virtual locations, they should be accurately disclosed.

More generally, trust is a huge concern in using VPN services, notably, with log retention. Users can measure download speed, they can verify access to geo-blocked content, but they have no insight into log retention – except when VPN users get busted. And it either comes out that logs were produced or that there were none to produce.

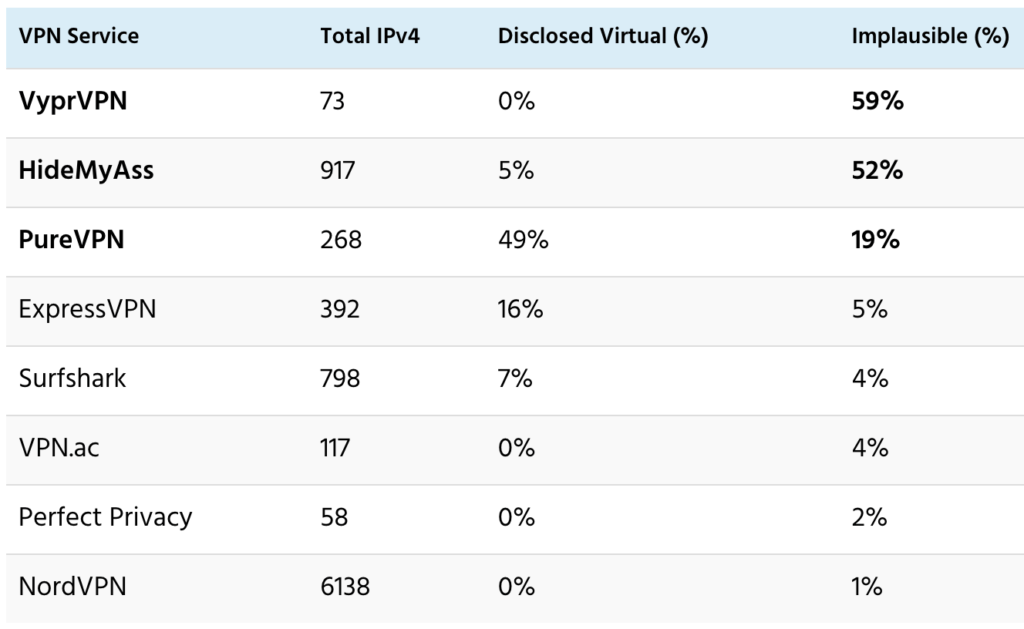

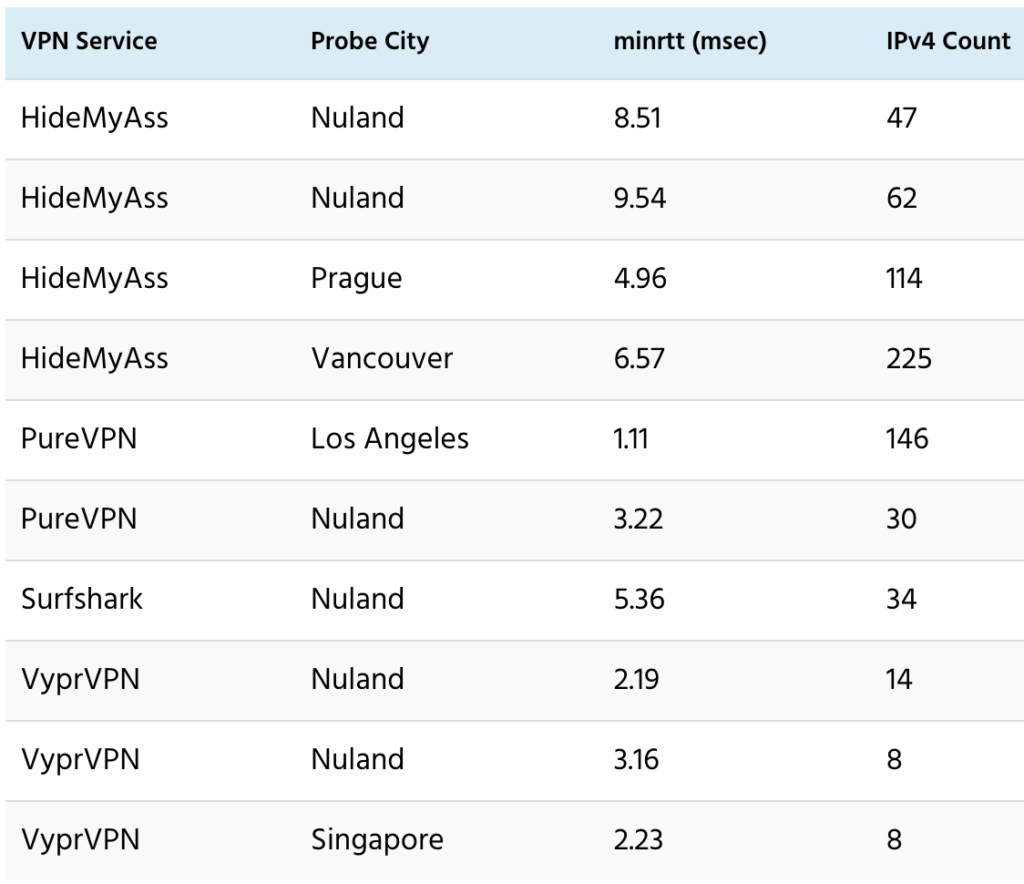

While both HideMyAss and VyprVPN disclose their use of virtual locations, there’s still a serious lack of transparency. I found that locations for over half of HideMyAss and VyprVPN IPv4 addresses are almost certainly virtual, and neither substantively discloses the number or identity of virtual locations.

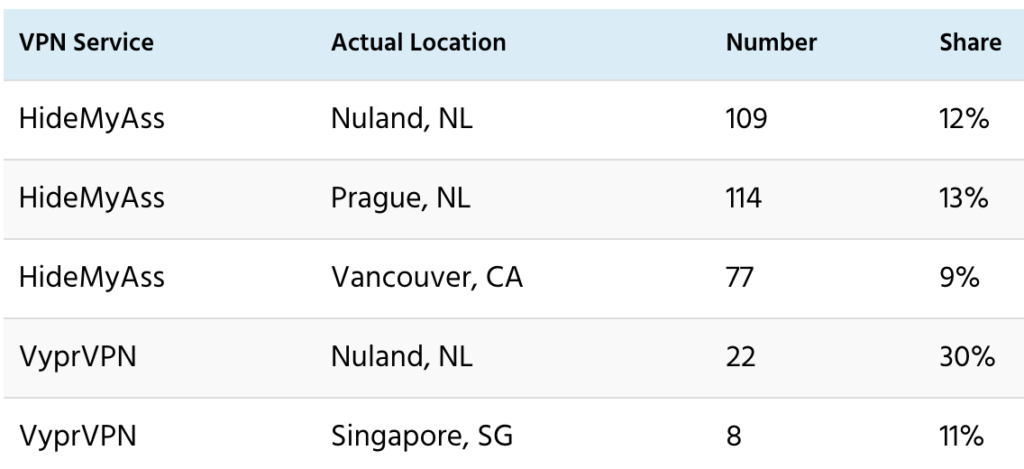

And it’s not just that virtual locations aren’t disclosed. It also appears that many of them share a few actual locations. For example, I find that 30% of VyprVPN’s IPv4 addresses are in or near Nuland, NL. And that 11% of them are in or near Singapore, SG. None of them are disclosed as virtual locations.

That’s also the case for HideMyAss. I find that 12% of its IPv4 that aren’t disclosed as virtual locations are in or near Nuland, NL. Also that 13% of them are in or near Prague, CZ; and that 9% are in or near Vancouver, CA.

Colocation is also an issue for disclosed virtual locations. For example, 59% of IPv4 for Surfshark’s disclosed virtual locations are in or near Nuland, NL. Also, 23% of IPv4 for PureVPN’s disclosed virtual locations are in or near Nuland, NL; and 22% are in or near Los Angeles, US. The key difference, though, is that Surfshark and PureVPN have disclosed these virtual locations, so users can choose.

As they say, “Lie to me once, shame on you. Lie to me twice, shame on me.”

If VPNs aren’t being honest about their servers, what else are they lying about?

Discovering Server Locations

One might think that it’s simple to discover server locations. There’s public data about server ownership (whois) and about supposed geographical locations of IP addresses (various databases, available through “what’s my IP?” sites). However, it turns out that those published geographical locations don’t necessarily correspond to actual server locations. Indeed, they aren’t actually used for anything! I’ll say more about that below.

So no, it’s not simple. However, using services intended primarily for monitoring web server reachability, we can ping VPN servers from probes in numerous locations. The ping utility measures the delay (round-trip latency) between sending test packets to another device through the network, and receiving replies. It reports simple statistics (latest value, minimum, maximum and average) and packet loss. Intermittent transmission delays can increase latency, so the minimum round-trip time (“minrtt”) is the most reliable measure of round-trip latency.

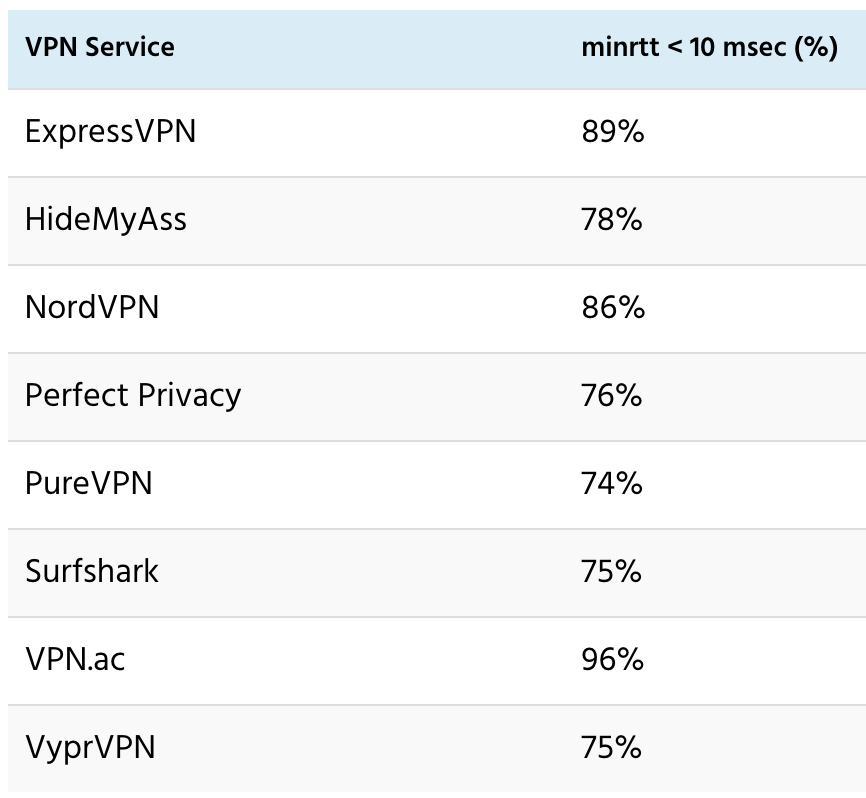

In doing this project, I collected over 250,000 ping measurements. That was necessary in order to find a ping probe for each server IPv4 address with minrtt under 100 msec, and ideally under 10 msec. But more about that later.

One might think that the probe with the smallest minrtt is closest to the server. However, there’s considerable uncertainty, because many factors affect site-to-site latency, and geographic distance is not necessarily the major one. In particular, the number of routers involved matters more than distance. And so triangulating locations using ping minrtt is entirely unworkable.

Even though we can’t reliably discover exactly where servers are located, we can test whether claimed locations are physically plausible.That’s because ping minrtt can be no less than twice the product of the great circle distance between probe and server, and the speed of light. All other factors that affect round-trip latency can only increase it. None of them can reduce it, for a given geographic distance. So if the calculated maximum signal transmission speed is faster than the speed of light, there must be an error in the location of the server, the location of the probe, or both.

How Virtual Server Locations Are Possible

The details are complicated, and outside the scope of this post. But basically, there are three levels of information about servers, and where they’re located. And they’re handled by different organizations, which don’t enforce consistency.

The bottom line is that a VPN provider can exploit lack of coordination among Internet organizations to hide the true locations of its servers. That is, a VPN provider can lease IP addresses owned by numerous ISPs, nominally located around the world. But it can announce them through the ISPs that actually provide Internet access for its servers. So traffic goes directly to them, regardless of the nominal locations of those IP addresses.

Autonomous systems (mostly ISPs) obtain IP addresses from Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). And the registrations do specify geographical locations. When firms configure their servers, they setup accounts with one or more ISPs, and lease IP addresses from them.

Independently, firms register domain names with various domain name registries. They provide organizational and contact information. And they also specify name servers, which map their domain names to IP addresses that their ISPs have delegated to them. The Domain Name System (DNS) hierarchy collects that information from name servers, and makes it generally available.

OK, so your machine discovers the IP address for some domain name, and initiates a connection. So then your ISP needs to know how to reach it. Its nominal geographical location doesn’t help. The ISP needs to know the best path, from router to router, across the Internet. It starts by discovering the autonomous system number (ASN) of the ISP that handles traffic for that IP address. Then it asks that ISP for directions, and gets a border gateway protocol (BGP) advertisement, which specifies the shortest router-to-router path.

But here’s the catch. When a firm arranges Internet connectivity with its local ISP, it can announce IP addresses that it’s leased from other ISPs, if those other ISPs agree. And then its ISP advertises the shortest router-to-router paths to the firm’s servers. So the ISPs that actually own the IP addresses aren’t involved in routing traffic.

Scope and Key Findings

I looked at OpenVPN servers for eight of the most popular VPN services, some of which claim thousands of servers, in hundreds of locations.

- ExpressVPN: “3,000+ VPN servers”, “160 locations”, “94 countries”

- HideMyAss: “We’ve got 1000+ VPN servers in 280+ locations covering 190+ countries around the world”

- NordVPN: “Choose from over 5,100 NordVPN servers in 59 countries and enjoy the fastest VPN experience.”

- Perfect Privacy: “… in 26 countries”, “Cascading of multiple VPN servers”, “No traffic limit”

- PureVPN: “Our global network of 2,000+ strategically placed servers helps you overcome any restriction.”

- Surfshark: “1,040+ servers in 61+ countries. … Strict no-logs policy”

- VPN.ac: “Affordable”, “Very fast and reliable”, “Multiple countries: 21 (VPN) …”

- VyprVPN: “more than 70 countries around the globe”, “over 200,000 IP addresses”

I relied only on location information provided by VPN services, on their websites and in OpenVPN configuration files. Six of the eight VPN services disclose locations at city level for 98%-100% of server IPv4 addresses. But ExpressVPN discloses city-level locations for just 65.0% of server IPv4, and NordVPN discloses no city-level locations.

Four of the eight VPN services disclose at least some virtual locations: ExpressVPN, HideMyAss, PureVPN and Surfshark. Although those disclosures seem accurate, as far as they go, this post will focus on server IPv4 that are not disclosed as virtual locations. While VyprVPN discloses that it uses virtual locations, it does not say which locations are virtual.

It appears that five of the eight VPN services have disclosed all or nearly all of their virtual locations:

- ExpressVPN

- NordVPN

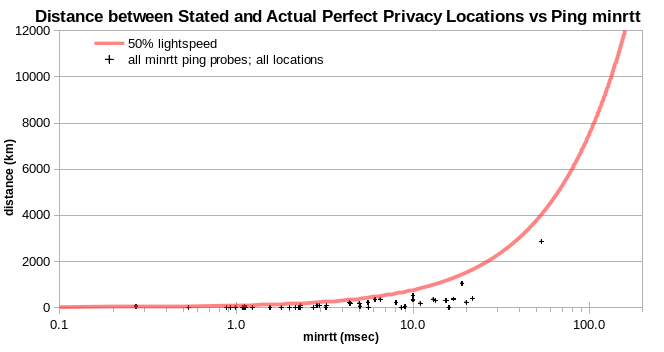

- Perfect Privacy

- Surfshark

- VPN.ac

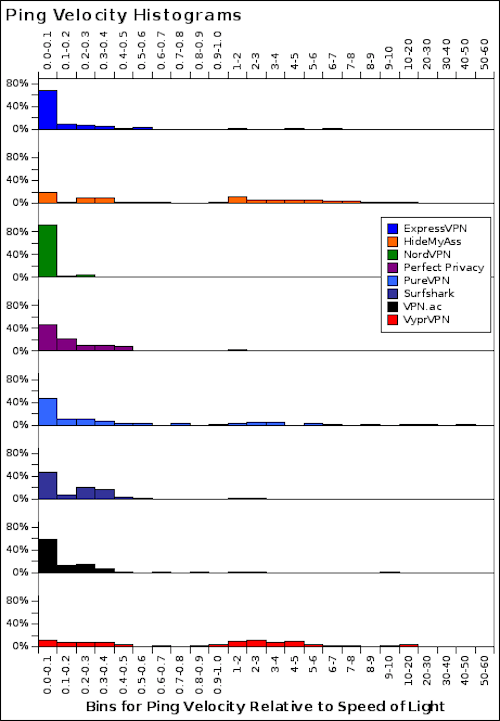

Three of those (NordVPN, Perfect Privacy and VPN.ac) disclose no virtual locations, and I see no substantial evidence for any. For all five VPN services, location plausibility (share of server IPv4 addresses with apparent ping velocity under 80% lightspeed) is greater than 95% for reportedly non-virtual locations. In other words, these five VPN services have disclosed all or nearly all virtual locations.

However, location plausibility for PureVPN is only 81% for locations not disclosed as virtual. But it’s at least arguable that the errors are inadvertent.

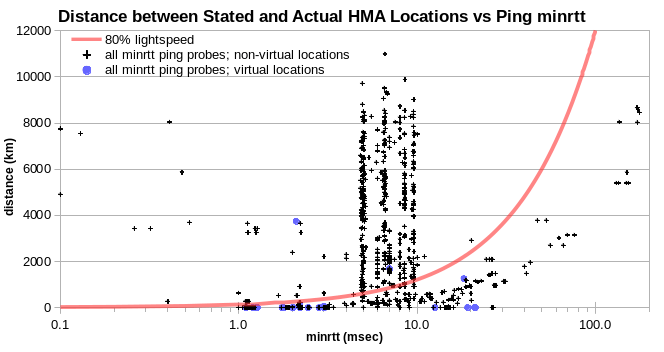

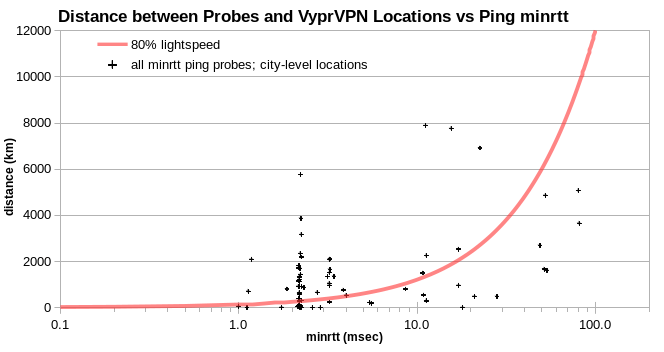

Conversely, VyprVPN and HideMyAss are in another league entirely. For them, less than half of reportedly non-virtual locations are physically plausible. Using 80% to 100% lightspeed as the ping velocity cutoff, just 48%-51% of HideMyAss IPv4 are physically plausible. And just 41%-48% of VyprVPN IPv4 are physically plausible.

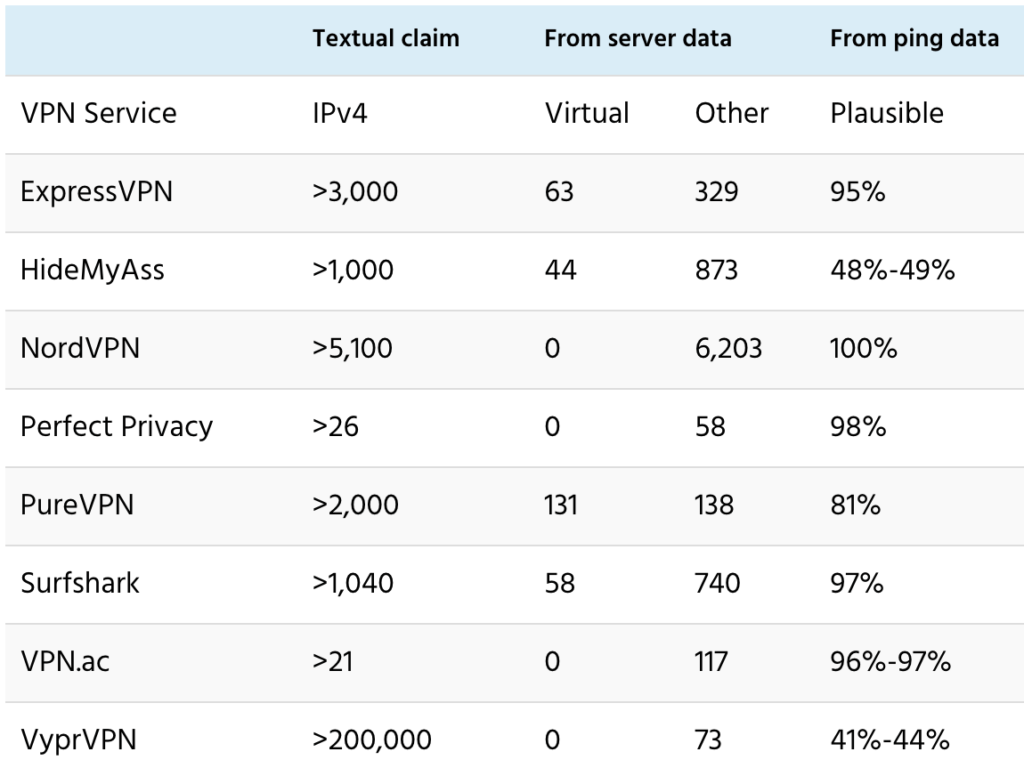

That’s summarized in the following table. It shows: 1) total IPv4 addresses that I found for each VPN service; 2) percentage disclosed as virtual locations; and 3) percentage of locations not disclosed as virtual with apparent ping velocity greater than 80% of the speed of light (which makes them physically implausible).

Histograms of ping velocity relative to the speed of light show these differences more quantitatively.

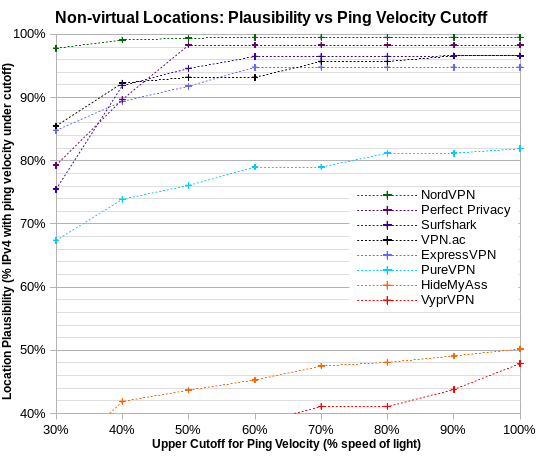

Sensitivity to Cutoff for Ping Velocity

We know that ping velocity can’t be greater than the speed of light in a vacuum. And we know that radio links through air are almost as fast, and that the limit in wire and fiber is on the order of 70 percent lightspeed. Although we don’t know the mix of link types, it’s arguably mostly fiber for long distances, microwave for intermediate distances, and fiber or wire for short distances.

As a sensitivity test, I looked at how the choice of ping velocity cutoff affects location plausibility assessments. In the chart below, you can see that the key results are not affected by the choice of ping velocity cutoff. The eight VPN services fall into three groups: accurate about virtual locations (ExpressVPN, NordVPN, Perfect Privacy, Surfshark and VPN.ac); less accurate (PureVPN); and inaccurate (HideMyAss and VyprVPN).

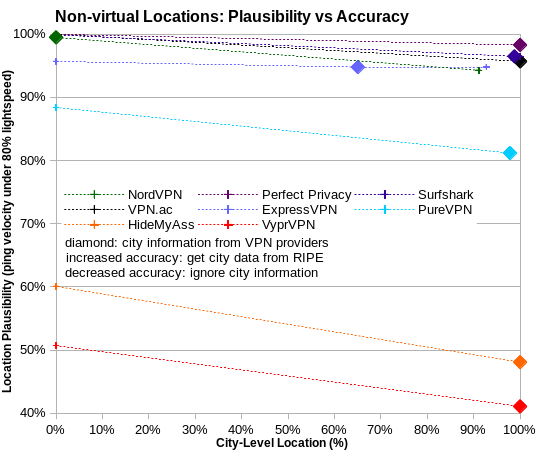

Sensitivity to Accuracy of Location Disclosure

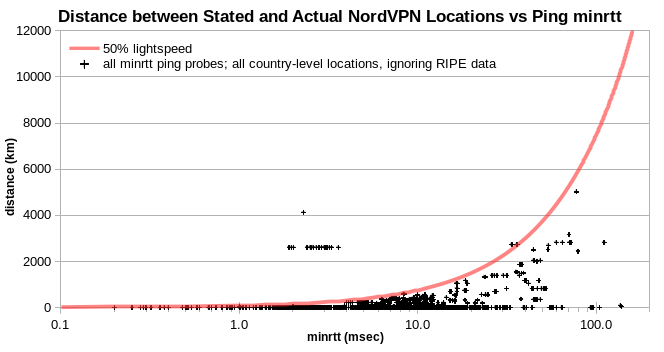

Although virtually all NordVPN locations are physically plausible, none of them are disclosed at city level. For large countries, that’s not at all accurate. When the lowest minrtt probe is in the same country as the VPN server, one must assume that it’s in the same city, so the distance is zero. And otherwise, one must estimate distance from the probe to the nearest border of the VPN-server country. That’s also an issue for 35% of ExpressVPN server IPv4 addresses.

However, differences in location accuracy don’t substantively affect the key results.

I explored the issue in two ways. First, I simply ignored city information provided for VPN servers. And second, I used location information from Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) to supplement provided city information. Using city information from RIRs decreased location plausibility to 94% for NordVPN, but had little effect for ExpressVPN. Conversely, ignoring city information increased location plausibility to 100% for Surfshark, Perfect Privacy and VPN.ac, but had little effect for ExpressVPN. For PureVPN, ignoring city information increased location plausibility from 81% to 88%.

Virtual Locations Appear Clustered

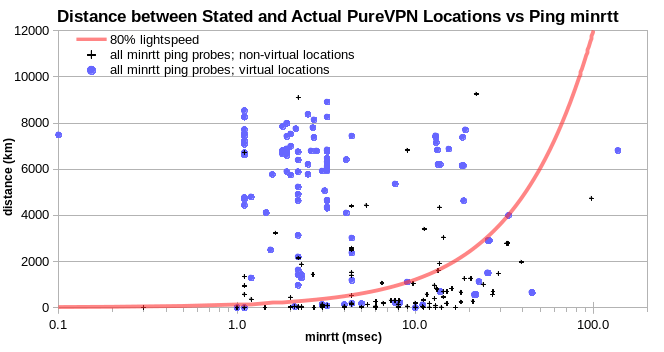

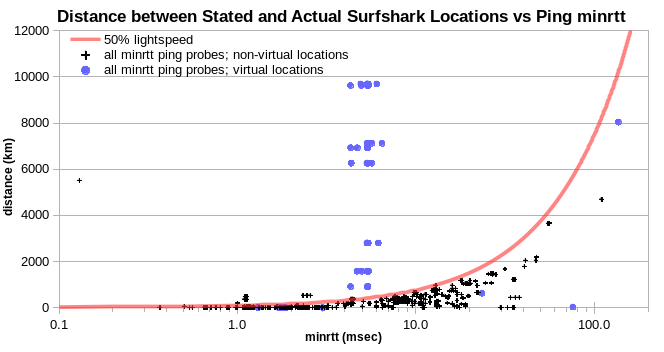

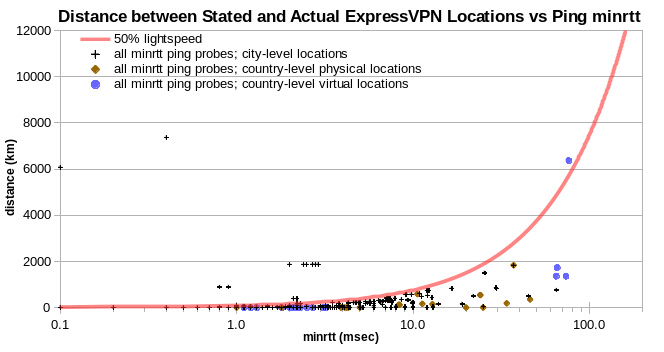

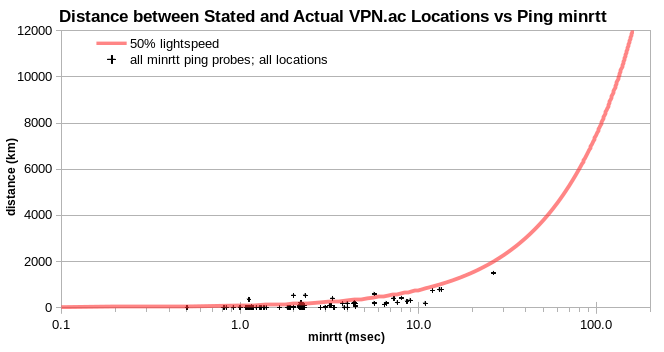

Disclosed virtual locations and physically implausible locations (which are arguably undisclosed virtual locations) are apparently often colocated. This is easiest to see in scatter plots of reported probe-server distance vs observed minrtt. IPv4 for physically plausible locations fall under a line at 80% lightspeed, and generally in the 30%-50% lightspeed range. In these scatter plots, I use log (minrtt) as the X axis in order to spread out the low range, which is most interesting. And so the lightspeed curves show up as exponential, rather than as linear.

It’s not surprising that virtual locations are clustered, because there aren’t that many data centers (DCs) with connectivity to Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and so to multiple networks. Also, IXPs themselves are often clustered, and are associated with a few nearby DCs and colocation facilities.

For PureVPN locations not disclosed as virtual, most of the physically implausible IPv4 are apparently colocated with disclosed virtual locations. That is, they fall in columns near particular minrtt values, with wide ranges of reported probe-server distance. Each column comprises data for just one probe location.

Analogous columns are evident in the Surfshark data, for disclosed virtual locations.

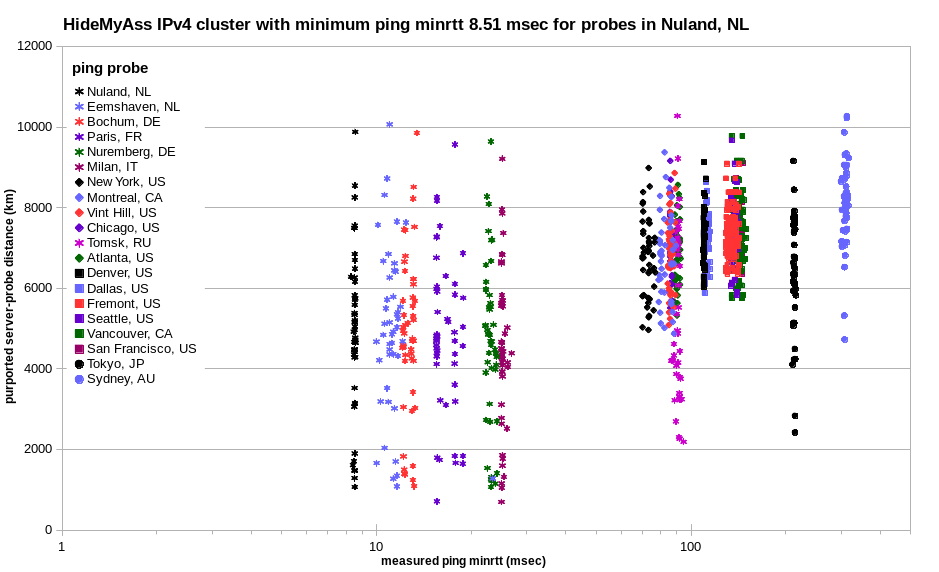

As with virtual locations disclosed by PureVPN and Surfshark, most physically implausible HideMyAss IPv4 also fall in columns near particular minrtt values, with each column comprising data for just one probe location.

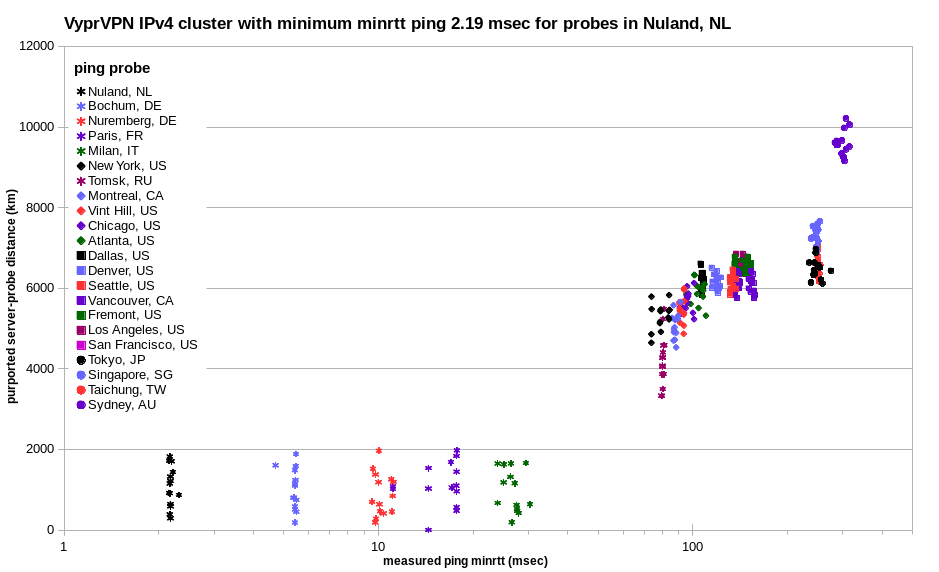

Analogous columns are evident for physically implausible VyprVPN locations.

It’s not always so obvious in the charts how many IPv4 appear in each apparent cluster. Because there’s lots of overlap. I identified ten apparent clusters, with hundreds to thousands of IPv4 each.

For the other six VPN services, there are few IPv4 above the 50% lightspeed line, and no such columns are evident. For ExpressVPN, there are a few physically implausible IPv4, but they’re not in columns.

Similarly for NordVPN.

There are no physically implausible IPv4 for Perfect Privacy.

And just a few for VPN.ac, with none in columns.

For example, I find these apparent clusters for virtual locations disclosed by PureVPN and Surfshark. The “Actual Location” column corresponds to the ping probe with the lowest minrtt. The “Share” column shows the share of disclosed virtual locations.

I also find apparent clusters for locations not disclosed as virtual by HideMyAss and VyprVPN. Here, the “Share” column shows the percent share of all locations.

Methods

Perfect Privacy connects to its servers by IPv4 address. But the other seven use hostnames. For them, I performed DNS lookups, using the Linux “host” utility, to get corresponding IPv4 addresses. Many hostnames resolve to multiple IPv4 addresses, and those might represent different servers, located in different data centers. And so, to ensure consistency, I collected ping data by IPv4, rather than by hostname.

This table summarizes information about IPv4 addresses. The “Textual claim” column is based on the website quotes at the beginning of the section “Scope and Key Findings”. Most VPN services don’t list numbers of server IP addresses. Given that, the IPv4 counts here assume at least one IPv4 address per server or location.

The two columns under “From server data” are based on server lists, names of OpenVPN configuration files, and/or server hostnames. The “Virtual” column shows IPv4 for locations disclosed as virtual, and the “Other” column shows the rest.

However, there may be multiple servers behind each IPv4 for load balancing. Therefore discrepancies between these numbers and quotes from VPN websites aren’t necessarily problematic.

The “Plausible” column under “From ping data” shows the percentage of IPv4 for reportedly non-virtual locations that are physically plausible, based on the ping data that I’ve collected, using 80%-90% lightspeed as the ping velocity cutoff.

For HideMyAss, NordVPN, Perfect Privacy, and VPN.ac, I find numbers of IPv4 addresses and locations that are more or less consistent with claims on their websites. For Surfshark, I find substantially fewer IPv4 addresses than expected, if each server has at least one IPv4 address.

But for ExpressVPN and PureVPN, I find only 13% of expected IPv4 addresses. And for VyprVPN, just 0.04% of expected IPv4 addresses. Using published hostnames, I did multiple DNS lookups for all three, over the course of a week or so. I also did that for HideMyAss. That yielded a slowly shifting set of IPv4 addresses for ExpressVPN, PureVPN and HideMyAss, but no substantive change in the address counts. And for VyprVPN, I consistently got the same 73 IPv4 addresses.

However, this is not the focus here. I mention it only to be as clear as possible about what IP addresses I’m reporting results on. Because I obviously can’t say anything about IP addresses that I didn’t test.

There are many reasons why I wouldn’t have detected and tested some IP addresses. I’m using an IPv4-only uplink, and so I can’t see IPv6 addresses. Also, there could be numerous servers behind each public IPv4 address for load balancing. And there may be numerous IP addresses that users can’t see, because they’re used indirectly as exits, to evade censorship and access geo-restricted content.

For each VPN server IPv4, I made an effort to find a probe with minrtt under 100 msec, and where possible under 10 msec. I used three ping-testing services: Ping.pe, CA App Synthetic Monitor (CASM), and MapLatency. Initially, I used headless Chrome to collect data from Ping.pe for each IPv4. That typically yielded data for 20-25 probes for each IPv4, depending on which probes were up, and which could reach the IPv4 being tested. Most IPv4 were unreachable from the 13 Ping.pe probes in mainland China.

I analyzed the Ping.pe data, and selected IPv4 where the lowest minrtt was greater than 10 msec. I then collected data for those IPv4 from CASM and MapLatency, accessing their APIs using headless Chrome. Over 60 “monitoring stations” are available through the CASM API. The MapLatency API provides access to thousands of probes, running on PCs, Android mobile devices, and DD-WRT routers worldwide. Given that, pinging each IPv4 from each probe would have been expensive and time-consuming. And also unnecessary. So for each IPv4, I selected nearby probes.

In selecting which ping probes to use, I relied on both claimed locations (from VPN service websites, names of OpenVPN configuration files, and server hostnames) and RIPE data reported in the Ping.pe tests. On average, I collected about 30 ping measurements overall for each IPv4. For those IPv4 where the initial Ping.pe run yielded a minrtt under 10 msec, there were as few as 20 measurements. And for those IPv4 with no low minrtt in the Ping.pe data, which were typically not in major cities, there were as many as 50 measurements. I identified probes with minrtt under 10 msec for 72%-96% of the IPv4 in the various VPN service datasets.

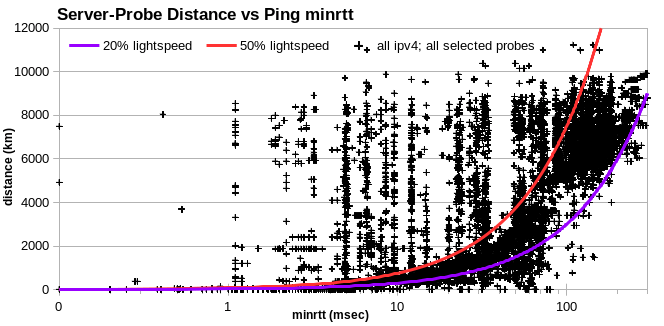

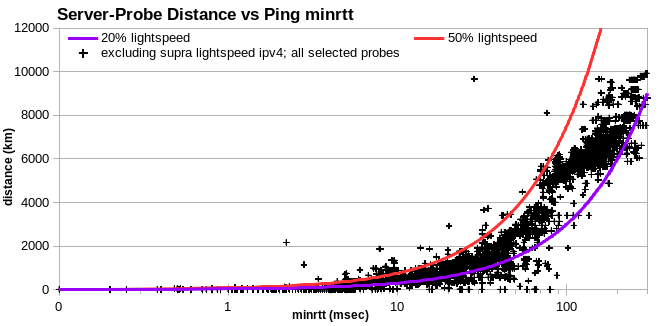

To check for mislocated ping probes, I extracted all ping data for probes that indicated an implausible location for any IPv4 in my analysis of minimum minrtt data for ExpressVPN, HideMyAss, NordVPN and PureVPN. Charting server-probe distance vs minrtt, much of the data lies well above the 50% lightspeed line.

However, if I drop the IPv4 with implausible locations, the data mostly falls under the 50% lightspeed line. So the probes that I’m relying on to identify implausible IPv4 locations don’t themselves have implausible locations.

More Evidence for Clustering of Virtual Locations

In scatter plots of reported distance vs observed minimum minrtt, most physically implausible IPv4 fall in columns near particular minrtt values, with each column comprising data for just one probe location. That’s also true for virtual locations disclosed by PureVPN and Surfshark. If the IPv4 in each column are actually colocated, they should also be clustered for other probes, and not just for the one with minimum minrtt.

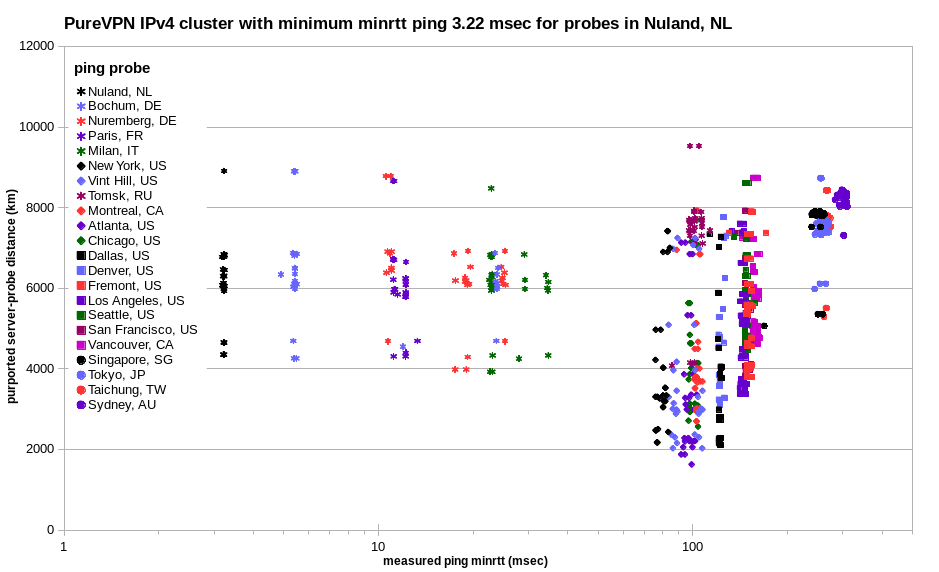

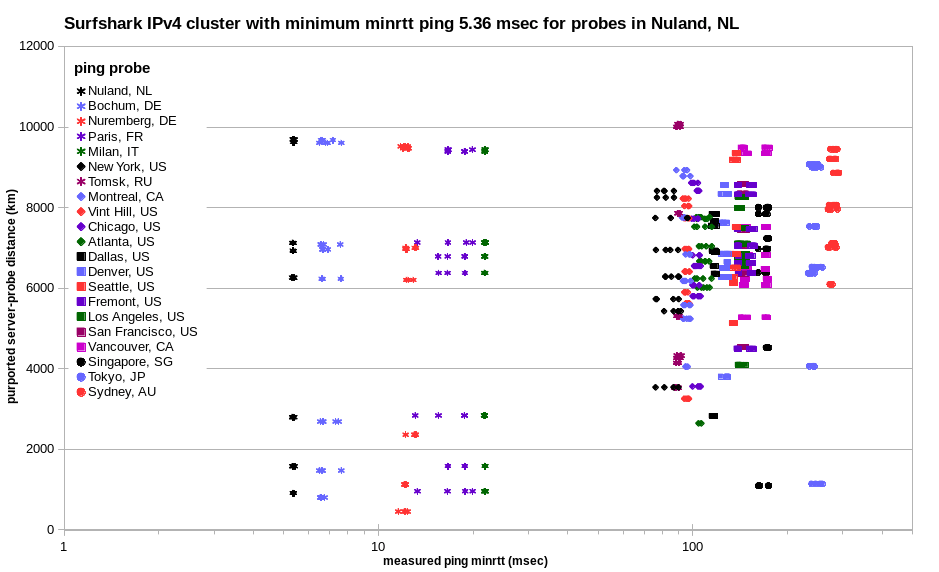

I looked at four apparent clusters with minimum minrtt for probes in Nuland, NL: HideMyAss and VyprVPN clusters in non-disclosed virtual locations, and PureVPN and Surfshark clusters in disclosed virtual locations. I pulled data for each set of IPv4 from the full ping minrtt dataset, and charted server-probe distance vs minrtt.

For PureVPN, the same IPv4 cluster is more or less evident for probes in numerous cities, in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. Scatter increases for more distant probes in Europe, but then is less for most probes in North America. Tokyo and Sydney are so far away from the virtual locations that the cluster collapses.

The result for Surfshark is similar, but there’s less scatter in Europe, and less cluster collapse in Tokyo and Sydney.

That’s also the case for HideMyAss undisclosed virtual locations. While there are many more of them, the cluster remains more generally well defined.

The results for VyprVPN undisclosed virtual locations looks a lot like that for PureVPN virtual locations, but with far greater distance shift.

It does appear that the IPv4 in each apparent cluster are actually colocated. Although there’s some scatter, many different probes show the same sets of IPv4 in columns. And the minrtt for each cluster generally increases with distance.

Assuming that each of those four apparent clusters are actually colocated in Nuland, I get a much simpler plot of server-probe distance vs minrtt.

Results for probes in the various regions are segregated. For Europe, there’s a group spanning 1-30 msec: Nuland, NL; Bochum, DE; Paris, FR; Nuremberg, DE; and Milan, IT. Then there’s a gap across the Atlantic, with apparently much faster transmission. I’m guessing that trans-Atlantic cables don’t have many routers. Next there are groups for eastern and western North America, with faster transmission than Europe, but slower than across the Atlantic. That probably also reflects router density. Last, there are jumps to Asia and Australia.

The fact that distances for Asia are only a little greater than those for western North America is at first surprising. Because the width of the Pacific Ocean is well over 10,000 km. But the minimum great circle distance between Nuland and Asia is only 6,000-8,000 km, heading eastward from Nuland. Even so, ping traffic, for whatever reason, clearly headed westward from Nuland, and across North America.

Conclusion

To wrap things up, here is an overview of my work for this article and the general findings.

- I collected over 250,000 ping measurements for OpenVPN servers from eight of the most popular VPN services.

- There are pros and cons to virtual locations. But even so, users deserve to know where VPN servers are located. And if there are virtual locations, they should be accurately disclosed.

- VPN providers can exploit lack of coordination among Internet organizations to hide true locations of their servers.

- While it’s nontrivial to reliably geolocate servers, we can test whether claimed locations are physically plausible. That is, if the calculated maximum signal transmission speed is faster than the speed of light, and locations of ping probes are known accurately, there must be an error in the location of the server. And server locations that aren’t physically plausible must be incorrect. Or in other words, virtual.

- Three of those VPNs (NordVPN, Perfect Privacy and VPN.ac) disclose no virtual locations, and I find no substantial evidence for any.

- Four of the eight VPN services (ExpressVPN, HideMyAss, PureVPN and Surfshark) disclose at least some virtual locations.

- VyprVPN vaguely discloses that it uses virtual locations (in a 2017 blog post), but says nothing about their number or identity

- Virtual locations seem to actually be clustered in a few cities.

- Overall, five of the eight VPN services (ExpressVPN, NordVPN, Perfect Privacy, Surfshark and VPN.ac) have apparently disclosed all or nearly all of their virtual locations.

- Over (59%) of Surfshark’s disclosed virtual locations seem to be in or near Nuland, NL.

- While PureVPN discloses that 49% of its locations are virtual, another 10% are arguably virtual.

- Almost half (45%) of PureVPN’s disclosed virtual locations seem to be in or near two cities (Los Angeles, US and Nuland, NL).

- HideMyAss discloses that 5% of its locations are virtual, but another 48% are apparently virtual.

- VyprVPN specifically discloses no virtual locations, but 59% are apparently virtual.

- Most of VyprVPN’s undisclosesd virtual locations (41% out of 59%) seem to be in or near two cities (Nuland, NL and Singapore, SG).

There’s no proper explanation of how they achieve virtual locations, how do they fool all the geoipdb providers?